This is the third post in a series on constructive alignment. The first is here.

Constructive alignment is a curriculum design principle grounded in constructivist learning theory, which posits that students actively construct knowledge through engagement with content based on their prior schemata. The “alignment” aspect emphasizes that assessment should directly correspond to the intended learning outcomes (ILOs), ensuring a criterion-referenced approach to evaluating student learning (Biggs, 1996).

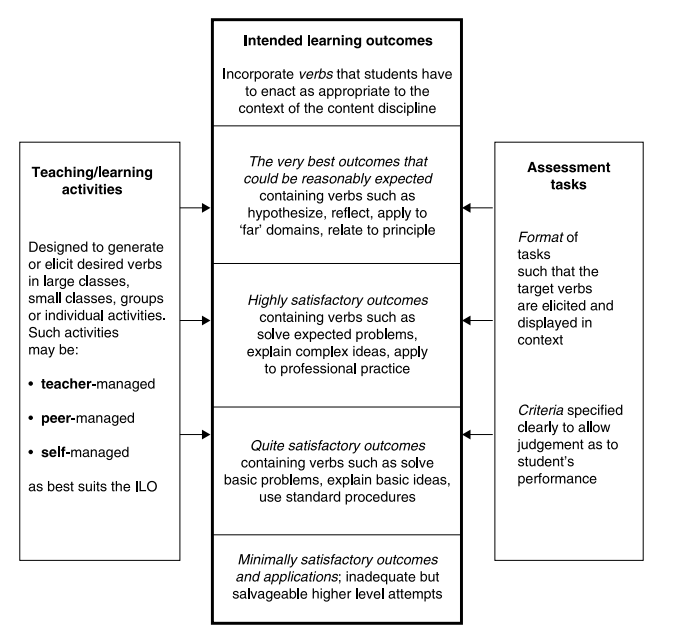

This approach to alignment operationalizes Shuell’s (1986: pg. 429) assertion that student engagement in learning activities is more critical to learning than teacher actions. Constructive alignment requires ILOs to specify the subject matter, and the cognitive process involved in attaining the skills and domains of knowledge outlined in the ILOs (e.g., “analyze X” or “apply theory to Y”). Teaching and learning activities (TLAs) must then facilitate these cognitive processes, and assessments must measure their achievement, ensuring consistency across instruction, learning, and evaluation.

Once the ILOs are established, it is important not to take constructivist epistemology to its extreme and expect the learners to work out how they will achieve the ILOs. As Biggs (1996) states on pg. 353, ‘…high-level engagement ought not to be left to serendipity, or to individual student brilliance, but should be actively encouraged by the teacher. In short, if good teaching is to stimulate competence rather than to reflect it, teachers need to activate an appropriately wide range of learning-related activities’.

The need for students to be active in their learning, characterized by the writing of outcomes that contain an active verb specifying what skills the learner will be able to demonstrate, has now become practically axiomatic in course design. This means that the ‘constructivist’ attachment to the approach is covered to a certain extent, covering all ranges and implications of schema development.

Biggs visualises the interrelatedness of the 3 components:

Logic prevails

In its essence, the alignment component is an exercise in logic, an exercise in eliciting consumer confidence: We’re saying that these will be the outcomes of your learning, we’ll provide the learning environment for it to occur, and then we’ll assess you to assure that you can in fact demonstrate the attainment of those outcomes. Significantly, this approach facilitates the learner’s ability to self-regulate their progress towards the outcomes: knowing that everything is connected means the learner can look backward to understand where gaps may have developed and forwards to know where their energies need to be applied.

There are four steps in designing such teaching and assessment, each of which will be discussed in more detail in subsequent posts:

- Describe intended outcomes in the form of standards students are to attain using appropriate learning verbs.

- Create a learning environment likely to bring about the intended outcomes.

- Use assessment tasks enabling you to judge if and how well students’ performances meet the outcomes.

- Develop grading criteria (rubrics) for judging the quality of student performance

It all sounds very simple, and in many ways, it is. However, education is a complex pursuit, and there are many conditions in which constructive alignment can seriously go awry. In the next post, we will discuss some common oversights when trying to implement it.

References

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High Educ 32, 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871

Biggs, J. B., & Tang, C. S. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university: what the student does (Fourth edition.). McGraw-Hill/Society for Research into Higher Education.

SlideShare. (2008). John Biggs And Catherine Tang 2008. [online] Available at: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/john-biggs-and-catherine-tang-2008-presentation/776584 [Accessed 1 Apr. 2025].

Shuell, T. J. (1986). ‘Cognitive conceptions of learning’, Review of Educational Research 56,

411–436.

2 comments