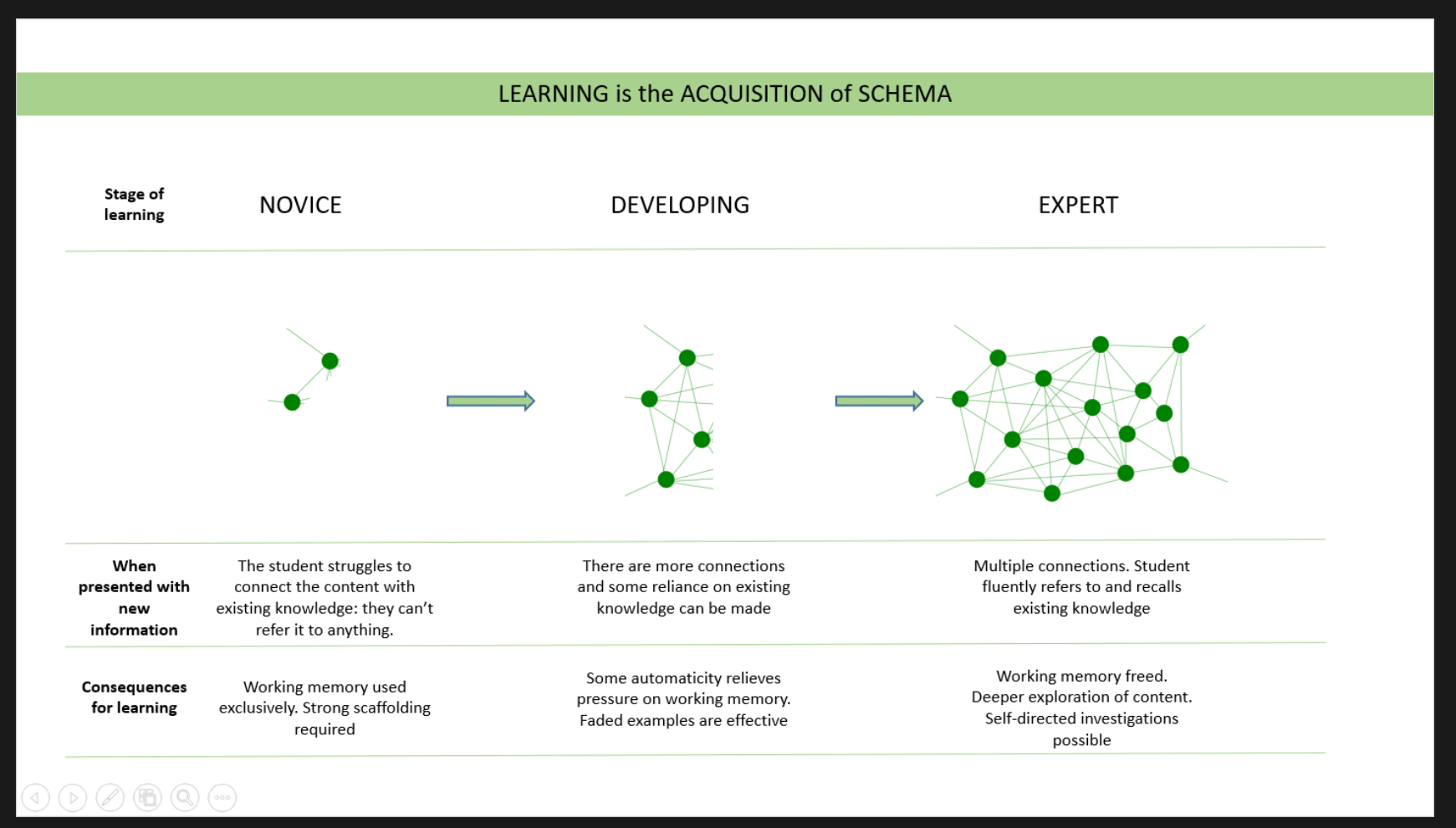

When we attend to information or stimuli in our environment, our brain goes through a process of assimilation, accommodation or cognitive dissonance. Whether the encoding is successful depends largely on how we can connect new content to already established ideas in our memory. It is this idea of ‘connection’ that is crucial. The brain stores information not as separate distinct items, as a computer hard drive would, but as webs of interrelated ideas. The notion of connection is furthered by Bjork et al who state that ‘We store new information in terms of its meaning to us, as defined by its relationships and semantic associations to information that already exists in our memories.’

It is this network metaphor that characterises how knowledge is stored about a given topic. The networked knowledge is called the schema of that topic.

The challenge in education is to sufficiently build a student’s schema on a topic. To do so, Bjork et al are again instructive: ‘(students) have to be an active participant in the learning process— by interpreting, connecting, interrelating, and elaborating, not simply recording. Basically, information will not write itself on our memories.’ Of course, the ultimate scholar is someone who can effortlessly move between schemata, understanding the connections between them so as to be able to apply the knowledge to new learning contexts, but this is certainly by no means an easy process to facilitate.

Undeveloped schema and problem solving

Before expecting students to answer complex questions or solve complex problems, it is necessary to develop a sufficient schema on the topic. Without this foundation, when the schema is searched for but can’t find a connection to the new content, it will experience cognitive overload. The more connected knowledge a student has, the greater the number of connections that the schema possesses, and this makes it easier for the brain to use the existing knowledge as a platform from which to process the new content. As each new learning moment adds in complexity, so the schema builds, and the ability to solve more complex problems with it. Carefully designing learning sequences that seek to incrementally extend from an existing and identified schema is a more efficient pedagogy if problem solving and applying learning to new contexts is the eventual goal of education.

The acquisition of schema is absolutely paramount to learning. The absolute key then is to know how sufficiently developed your student’s schema is before you design your curriculum, and then your learning sequences.

I’m Paul Moss. Follow me on Twitter (@edmerger) or on LinkedIn for more discussions about learning design.

3 comments