Teaching creative writing can be incredibly difficult. I’ve discussed some of the issues previously, but the most frustrating I think is when students suggest they aren’t creative and so justify to themselves not doing any writing. The inevitable disruptive behaviours then can become a nightmare to manage. In this post, I will introduce a pragmatic approach I’ve adopted, with success, in getting students to produce quality responses in specific time frames.

Students who withdraw from the writing process undoubtedly lack the confidence to write, which is because they lack the tools to do so. There are numerous commentators who implore teachers to provide consistent opportunities for students to write, thereby building their confidence in the process and concurrently developing a love of writing. Chris Curtis‘ notable 200 word challenge is a prime example, where students are encouraged to write from a prompt but crucially without the fear of it being marked within an inch of its life, avoiding any self-consciousness and allowing a freedom of thinking. The English and Media Centre’s ‘Just Let Them Loose’ echoes similar sentiment, beseeching the need for students to write on their own terms.

Whilst I completely advocate these approaches, I also know that they require a dedicated and deliberate curriculum design to consistently give students the opportunities to write and slowly build self-regulatory skills in knowing how to strengthen their ability. Possibly because these understandings haven’t filtered through the years yet, unfortunately, quite often when students enter my GCSE classes, many still have significant gaps in their creative writing. They have missed the developmental approach in KS3 and KS2, and because of the ridiculous pressures of the GCSE exams, I have to compromise with the above expressive strategies. I have to provide students with a writing structure to engage creative writing.

This scaffold eliminates the opportunity for a student to not produce any writing, but also arms them with a tried and tested formula that can then be used as a base from which to begin the expressive journey that the above strategies espouse.

SCAFFOLDING WORKS

To begin, I wanted to demonstrate that the structure I was going to propose they follow was an effective one. There is no better way to do that than actually reading successful stories to them. Such stories have been gathered over the years, and have been collated here (PS – I’d love to add more stories to this if you have some). Pragmatically, the stories are based on the GCSE creative writing task, around 45 minutes worth of writing – this is a crucial idea: everything I expose them to should be a model they can follow to satisfy the 45 min task. Again, thinking pragmatically, I am beginning to think more and more that the key for success is develop deeper understandings by limiting the type of writing students do – that is, getting better at less rather than spreading efforts too thinly (blog pending).

With interest piqued from the read out stories, I introduced the process:

- Provide images as prompts with the intention of slowly removing them so eventually only worded prompts are necessary

- Provide writing structure scaffold

- Provide a written story with comprehension questions to build structural knowledge

- Tell students they need to complete 2 stories before the assessment – kind of like a controlled assessment – one using the prescribed structure and the other of their own choice, for the sake of evaluation. This means that students can decide which structure they prefer to write with

HERE IS THE SEQUENCE IN ACTION

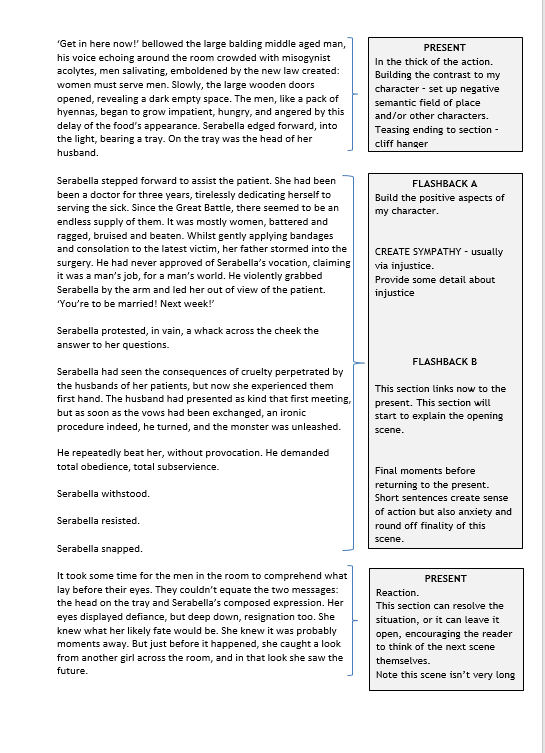

I presented a provocative image to spark thinking – one that included a character. The image opposite is superb.

I then introduced the 4 section story:

- Intro – begin in the middle of an action or scene of intensity. The important thing here is to emphasise a particular tone that the main character is experiencing – negative or positive. The ending of the intro could introduce a cliff hanger to tease the reader, as the next section will not explain it immediately.

- Flashback A – this is a chance to connect to the character affected by the action in the opening. Contrast is essential, with the reader taken back into the character’s life that was either going along really nicely (contrasted to negative opening) or badly (contrasted to positive opening). This section doesn’t have to relate to the opening, and I think this provides a relief to the reluctant writer as they can simply develop the character without bounds.

- Flashback B – this is the beginning of the sequence of events that eventually take the reader back to the opening scene. By the time we finish this section, the opening would then make sense. A conflict is introduced, that contrasts, again, with the positive or negative tone created in flashback A.

- Ending – this doesn’t have to resolve the plot. It can incorporate aporia, a sort of ellipsis, either leaving the reader wanting to know more, or simply ending things without a feeling that all is restored or ok. I write about such a fatalistic tone in Macbeth and other texts here. This idea of aporia is crucial because I think this is where many struggling writers become unstuck – feeling that their ending has to rock the world, feeling like they need to satiate the traditional narrative arc.

WRITE YOUR OWN STORY – this process is crucial, so you get a sense of what the process is like, and can then discuss and show students yourself how to do it. The confidence with which you model will give your students great confidence too, knowing that they can trust your ability.

Below is a model story I wrote, available here. I live modelled the beginning, and then gave them the story. On the right hand side I have explained each section’s purpose, offering them a template to use for their writing.

To help develop a better understanding of the process I realised that students needed to have a good understanding of the story – I needed to test their reading: first their comprehension of the plot, but also how the story had been designed (questions below). I wanted to expose the students further to the mechanics of the writing, to delve into the purpose of each section.

EXTRA SCAFFOLD – SENTENCE SCAFFOLDS

As I’m sure you’ve experienced, students often can’t get started. As a solution to this, but also to consolidate the comprehension and knowledge of the design of this approach, I gave them a grid to complete that would provide a rationale for EACH sentence. The purpose of this is to provide a mood scaffold (3rd column) as well as a structure within the structure (last column).

Once this first model has been worked with, more images are used for students to practice the process. More likely than not, which I think validates this approach, you may need to continue with the modelling, writing another story yourself with a new image and taking students through the scaffold.

When we see students needing more than one experience of the modelling process, it reminds us that it’s not easy to write a successful story, and it takes lots of practice. Not just the inexperienced teacher would be guilty of rushing the process and have students writing independently too quickly, especially when exams loom.

Critics of this approach would cite that the very prescriptive aspect of the strategy smothers the freedom of expression that makes writing such a wonderful artform. My response to this is threefold:

- Firstly, pragmatics must drive strategy when students have missed necessary developmental time in previous years

- Secondly, the strategy is not designed to be the only writing technique, but a base from which students can develop personal style.

- Thirdly, because it takes a long time to become a strong writer, students may be better served in getting strong at one style before trying others. Developing one style well I think is better than what weaker writers end up with when left to their own devices – which is nothing.

I’m Paul Moss. Follow me on Twitter @edmerger, and follow this blog for more English teaching and general educational resources and discussions.

This post is featured by Twinkl in their ‘Teaching Writing’ blog.

Thank you for this Paul – it’s a better, more developed version of something I’ve been trying with a Y11 class that had no consistent teaching last year. Disengaged and refusing to write. You’ve confirmed my instincts about how I might pragmatically develop their skills with exams looming. It’s encouraging to see you’ve used this successfully! Many thanks.

LikeLike

Thank you Joanne. Let me know how you go

LikeLike

Thanks a lot for the information

What you said is so true.

Some unfinished stories that I have created .

I need to hear this to be more motivated

LikeLike