Assessing for learning needn’t be signposted by explicit formative tasks. Formative assessment can be implicitly woven into your teaching, and this can be achieved by using continuous retrieval practice. *

Asking questions in class/lectures/tutorials is a form of retrieval practice. The questions actively force the brain to try to recall the knowledge, and since understanding is memory in disguise, this strategy is an excellent way of assessing whether what you’ve taught your students has actually been learnt. Questions needn’t be verbal: they are any form of interaction that demands a student to fill in a gap.

Nuthall’s research found that for students to be able to understand a concept, they needed to be exposed to the complete set of information about the concept on at least 3 different occasions. This has enormous implications for how we teach, because in order for us to be able to assess for learning, we have to provide adequate opportunity for students to actually encode the information. Bearing in mind that attention is necessary to constitute a single exposure (as without actually attending to something it is impossible to encode it), and that sometimes student attention can waver (oh, is that a fly on my page), we may in fact need to increase the number of times we facilitate their exposure to necessary and important content. Continuous retrieval practice then not only challenges and thus strengthens the neural pathways the information is stored in, helping secure that content into the long term memory, but also provides another exposure of content to students who haven’t reached the magical number 3 yet.

Without using retrieval, the teacher can’t be sure the knowledge is secure in the student’s mind until they use a more formal assessment. But by this time, there could already be large gaps in the knowledge base that will take longer to unpick, and undoubtedly prevent the student being able to understand the next sequence in any sort of depth. This may manifest in the student who appears to be always struggling to keep up.

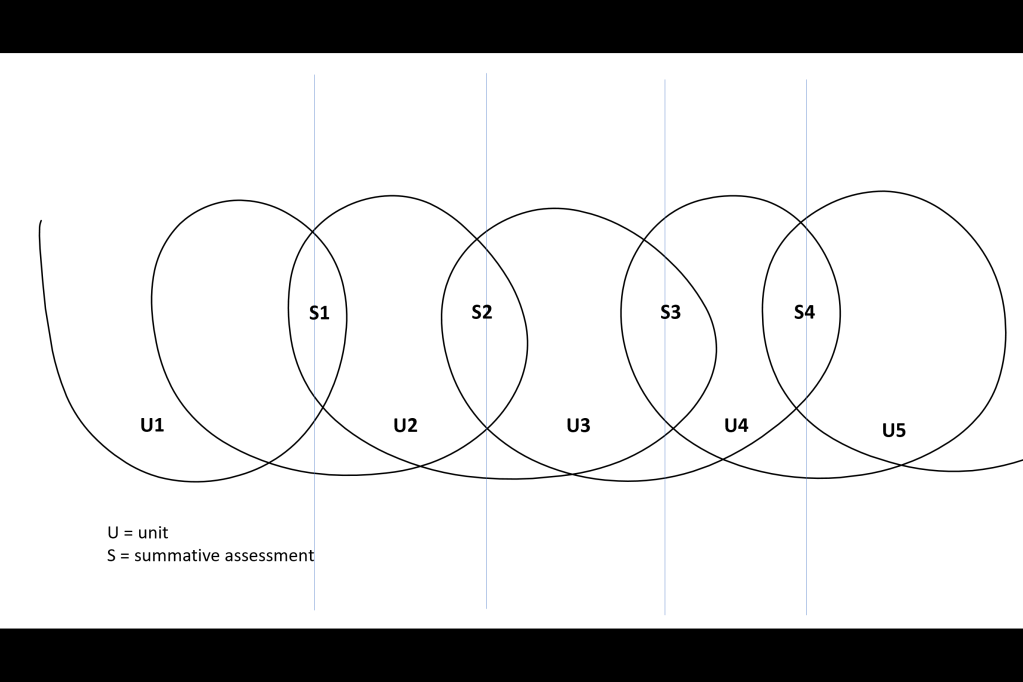

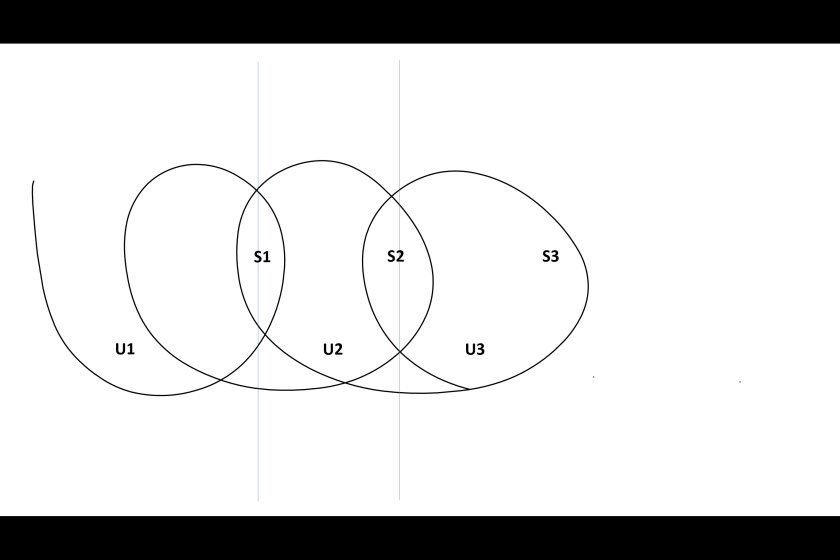

Assessment then should be seen as a continuous but incremental method of checking for learning, as depicted in this image:

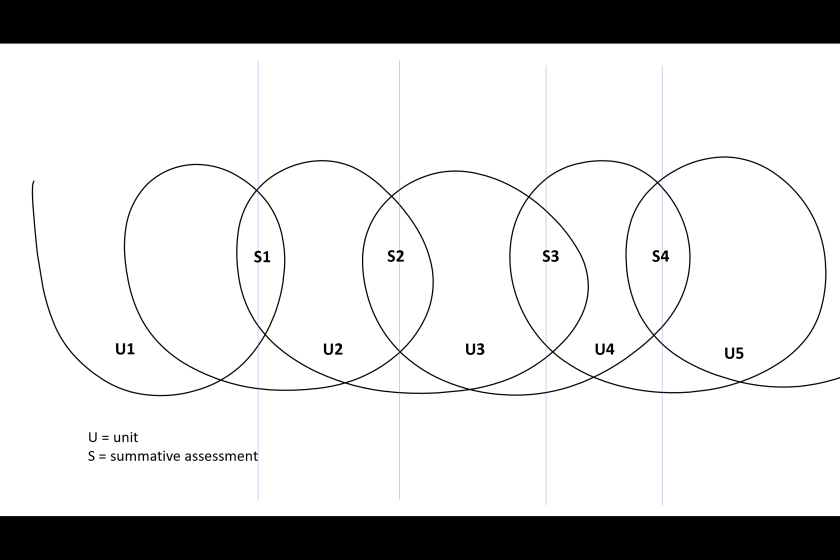

The above graphic represents 5 units (U) of work in a course. The metaphor is that when a unit is taught, retrieval practice is embedded (looped back) into the unit before moving onto the next: the teacher explicitly focuses student attention on key aspects of the unit that are essential and requisite knowledge for the next. A summative assessment (S) measures student knowledge at the end of the unit. When the next unit is taught, the retrieval practice not only focuses on the content of the 2nd unit, but also the summative content of Unit 1, as the spiral for U2 overlaps at the S1 sector. The process continues, but crucially, each subsequent unit must draw from every unit previously taught.

Let’s look at this more closely:

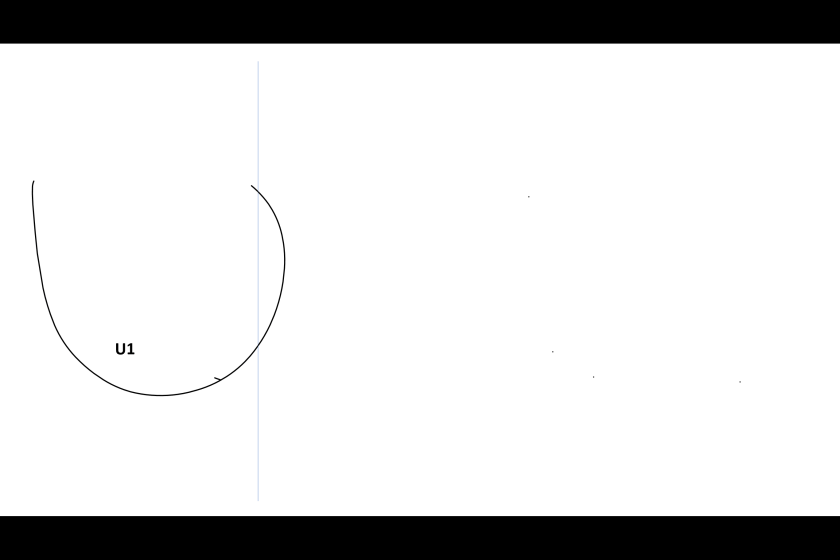

Figure 1

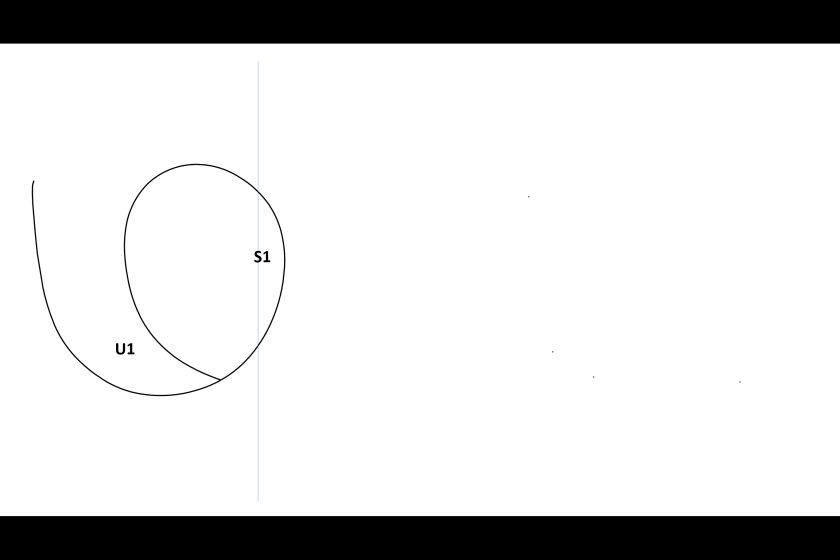

Figure 2

Figure 1 represents the content taught in Unit 1. Figure 2 represents the retrieval process in Unit 1 with the loop feeding back into the shape.

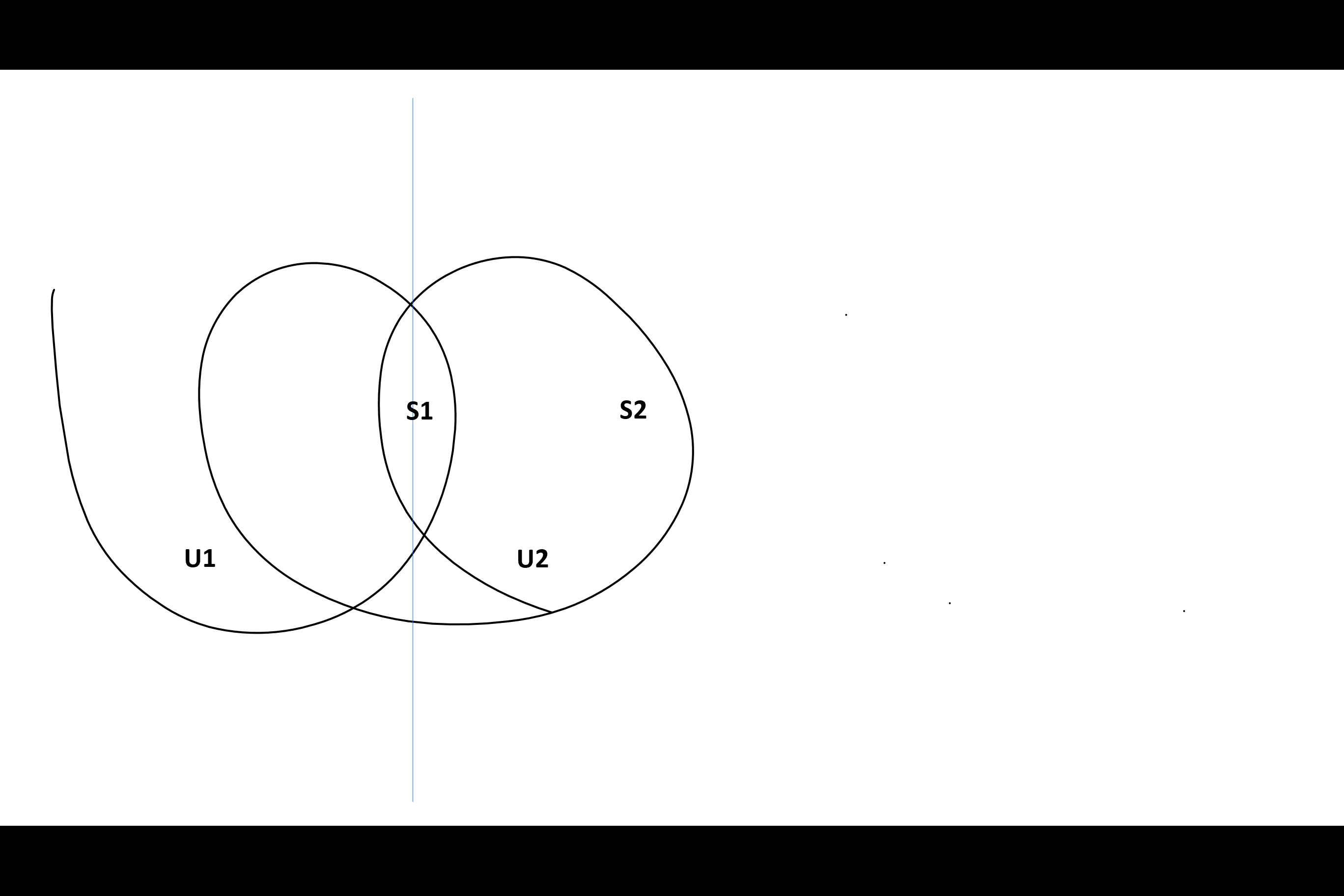

Figure 3

Figure 3 represents the teaching of the second unit. But critically, the summative content (S1) from Unit 1 is very much a part of the sequence. That, as well as the new content of Unit 2, now forms part of the summative content (S2) for that unit.

This design is very deliberate. It stems from an awareness that the exposure to the new information must incrementally build on what the student already knows. Willingham (p6) suggests that when posed a problem, our brains search** for solutions by invoking previous knowledge about a topic or at least something related to it, both declarative and procedural. (This by the way, is why worked examples are so integral to effective teaching practice.) The thinking about the previous knowledge and how it fits with the current knowledge is how we begin to develop schema. Without this precise design of a sequence of learning, the schema can’t form, and this has large implications for teaching new content.

Of course, you won’t be able to test all of the content at each summative (S) point, but this is where spaced retrieval comes into play. Spaced retrieval not only helps you to plan to incorporate all the relevant content over the duration of the course, but perhaps more importantly, it helps students to learn the same amount of content without having to put in extra study. It’s simply a very efficient use of study time.

Figure 4

Figure 5

The process continues until all units have been taught (figure 5), with each new unit drawing from and incorporating previous learnt material as part of the new sequence. At the very end, a final summative test is given, but as you can probably deduce, it will be not that different from what has been happening all the way along. It may simply be a longer test. The likelihood of success in this final test/exam will be significantly higher as students have been given multiple opportunities to access the content over the course, facilitating the movement of knowledge into the long term memory, and very much reducing the enormous anxiety that exams can create, and the criticism of their validity.

Well this is OK in a classroom or a tutorial, but what happens when I have a lecture with more than 40 students I hear you ask? Can I still use this approach? That’s the topic of the next post

In the next post I will outline the ways formative assessment can be applied in HE

*I know that retrieval.org suggest we shouldn’t view retrieval as an assessment strategy, but rather as a learning tool. I think though that teaching is essentially broken into 3 parts: delivering content, assessing its understanding, and influencing emotional intelligence. I see every question we ask as a tool to assess and to inspire thinking.

**I am aware that the tangible processes I discuss are indeed metaphoric.

I’m Paul Moss. Follow me at @edmerger

One comment